VIOLENCE SHAKES THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC IN 2017

In 2017, violence in the Central African Republic (CAR) has become increasingly intense, resulting in disastrous consequences for residents. Currently, just over half the population find themselves in need of humanitarian assistance. Ewelina Gasiorowska, Première Urgence Internationale’s manager for the Africa region, sheds some light on the situation.

IN 2017, WE ARE SEEING INCREASING VIOLENCE IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC. HOW DID SUCH A SITUATION DEVELOP IN THE COUNTRY?

Violence in the Central African Republic has grown in scale, although in truth, in recent years, the country has not truly known periods of calm. The situation became highly unstable, resulting in crisis after crisis, following the coup d’état in 2013.

Within the country, there are a number of different and long-standing conflicts. Their intensity varies over time, and they have a major impact on the population:

- Ethnic conflicts, such as in the north-east of the country, between the Gula and the Runga people.

- Problems between the Northand the South of the country

- A cultural conflict between ‘Arabs’and Bantus

- A community-based and religious conflict between Christians and Muslims

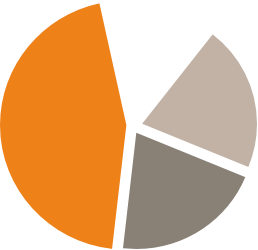

The crisis between Christians and Muslims did not exist before the 2013 coup d’état. It has resulted in a number of acts of violence and large population displacements in the Central African Republic, both within and outside the country. In September 2017, there were around 600,000 displaced persons within the country and around 500,000 refugees.

Violence in the Central African Republic is the result of increasing confrontation between different armed factions. These groups are also growing as a result of alliances between their members. These alliances are made and broken based on the interests of each party, such as conquering and controlling mining areas or forests.

The situation has worsened since 2017. Areas that have until recently been relatively stable have become home to crisis. In the last few months, the north-east and south-west of the country have seen unprecedented violence.

WHAT CONSEQUENCES WILL THIS VIOLENCE IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC HAVE ON THE POPULATION?

Currently, two thirds of Central Africans do not have access to primary healthcare. Almost half the population eat only one meal a day. These figures reveal a population in extreme suffering. Armed conflicts result in violence against the civilian population that is fleeing the combat, often returning to find their homes have been pillaged.

The international community, which maintains a presence in the country, is also affected by the violence. Recently, a health centre managed by humanitarian agencies was attacked. Convoys carrying equipment and supplies are regularly attacked, and aid workers experience difficulties accessing populations that are in need.

WILL THIS VIOLENCE IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC CONTINUE?

The CAR is at risk of a flare-up of violence. In Bangui, for example, residents are very tired and frustrated by the situation. At the end of November, a traffic accident resulting in the death of a student triggered a wide-ranging series of demonstrations in the city. The situation is unstable and fragile.

We have also noticed a growing ‘anti-NGO’ sentiment. The population is not seeing any improvement to their country’s situation, and does not understand why Westerners are in the country.

SO IS THE HUMANITARIAN COMMUNITY EXPERIENCING DIFFICULTIES WORKING IN THE FIELD?

Access difficulties that NGOs are experiencing, whether for reasons of humanitarian space or logistics problems, make it difficult to support the population.

It’s also essential to work with the population and with the authorities on raising awareness of humanitarian principles in order to ensure that NGOs’ and UN peacekeepers’ mandates are fully understood and that there is no confusion between the two.

NGOs need to negotiate humanitarian access. They also need to coordinate themselves to ensure their work is as complementary as possible. Pooling resources is key. For example, in Bangui, we have developed a warehouse project. This allows humanitarian stakeholders to store humanitarian equipment and supplies in a secure location before being sent to the country’s provinces.

Première Urgence Internationale is also implementing a pilot project providing logistics assessments and support to warehouses located outside the capital.

In the CAR, it is difficult to predict where will be affected by violence or mass population movements. What is a stable area today can become a hotbed of violence overnight. We need to be able to provide a rapid response to populations in need.