SOUTH SUDAN: VITAL ACTION TO FIGHT AN UNPRECEDENTED CRISIS

South Sudan is a new nation, born in July 2011 after gaining independence from Sudan. Ever since its creation, the country has been one of the poorest in the world, with a weak economy and infrastructures, a high mortality rate among mothers and children and very widespread malnutrition.

In December 2013, violent fighting broke out after an attempted coup d’état. Since then, the country’s situation has remained highly unstable. In November 2016, there were 1.83 million displaced persons within the country, 1.3 million refugees in neighbouring countries and 261 541 refugees in South Sudan because of instability in their country.

Première Urgence Internationale has been working in the country since 2015 and, facing an ever more critical situation, has recently decided to carry out an overall evaluation of the situation in the Bahr al Ghazal region to respond in the best possible way to the population’s needs. Water, sanitation and hygiene, health, nutrition and food security are the different sectors studied by the organisation’s experts. The results of this evaluation are clear and irrevocable: needs are considerable and it is vital to react quickly to avoid the situation deteriorating further.

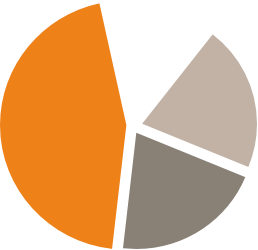

In fact, according to the data recorded, the majority (61%) of the population is very vulnerable and in urgent need of aid, particularly for health, nutrition and food security. The overall rate of acute malnutrition is rising to 40.6% of the population. Malnutrition in pregnant and lactating women is also high with nearly one woman in two suffering from malnutrition. According to the network of early warning systems for famine, the country has reached a level of 4/5 corresponding to an emergency and is likely to reach the famine stage of 5/5 without humanitarian intervention.

Lack of food is forcing more than 80% of households to eat ‘wild foods’, to reduce portion sizes to give more to the children and to regularly go without food for a day or more.

The multi-sector evaluation has also shown that local agricultural production is too weak to respond to the population’s needs. 100kg of cereals are produced each year per household, whereas at least 1022kg are needed. This poor level of production is due to several factors: shortage of seeds (from poor production in previous years), shortage of equipment (tools, irrigation equipment, ploughs), the prevalence of many parasites, poor soil quality and climatic changes. Spiralling inflation also continues to be a major challenge (the country’s annual inflation rate was 425% last February).

For Mauricio Tautiva, Première Urgence Internationale’s water, sanitation and hygiene advisor, the situation is particularly critical in terms of food security: ‘There is no food left; they are reduced to eating the leaves from trees, and roots with sorghum’, yet sorghum stocks are only secure until May, and the next harvest will only take place in October. In the next few weeks, there will be no food left for the population, and more and more people will be likely to leave to go in search of food, particularly to the neighbouring Sudan in the Darfur region.

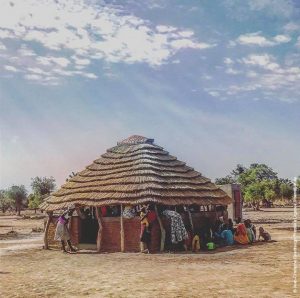

Access to care is also a major problem facing South Sudan’s population. In the area where Première Urgence Internationale is intervening at present, its teams are working in a health centre serving as a hospital with 6,000 to 8,000 appointments per month, and sometimes 10,000 when malaria hits a peak. The organisation is also offering free health care and access to medication in a larger area. The quality of the teams’ work is particularly well-known, and so people sometimes come from far away to be seen. It takes an hour or more for over half of all families to reach a health centre. Unfortunately, conditions for working and being cared for there are still sometimes rudimentary, as institutions face a shortage of medication, of human resources and of equipment. It is therefore essential that access to health care is improved for this population prone to many pandemics and to malnutrition.

‘In South Sudan, humanitarian aid has real meaning; it gives us extra motivation for our work’, stresses Marie-Michèle Thiam, Première Urgence Internationale’s African health adviser.

Last of all, access to water is also critical with very few access points to safe water. Because of this, 74% of the population needs to walk for more than 30 minutes to reach a water point, and 57% must even walk for more than an hour. The population needs to go to these water points 3 or 4 times a day in temperatures of 45°C. This problem directly affects the population’s nutritional status, as they expend a significant amount of their already limited energy reserves going to fetch water. Access to quality water and decent hygienic conditions are two more challenges that the country must overcome quickly.

Faced with this particularly dramatic situation, Première Urgence Internationale, like many other organisations, is taking action and wants to step up its work to bring the necessary aid to this population, victim of one of the forgotten crises throughout the world.

On this subject, please watch this report by The National, a programme by the Canadian television channel CBC, where you will be able to see an interview with Agnes Acheng, Première Urgence Internationale’s nutrition programme manager: