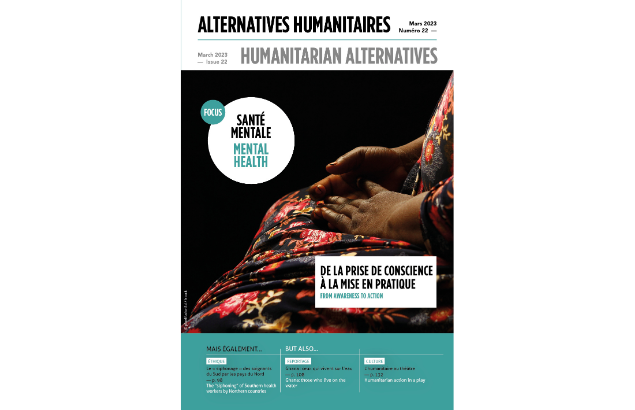

Understanding mental health to improve action in crisis areas

Alternatives Humanitaires (AH / Humanitarian Alternatives) magazine has dedicated a whole report to mental health in its latest issue of spring 2023. For too long, mental health has been considered secondary, while it should be a key concern in humanitarian action.

Populations exposed to armed conflict, natural disasters, pandemics or economic collapse suffer shocks that can have a serious impact on them throughout their lives. Aid workers are also exposed to high levels of risk every day in the field. This requires employers to invest significantly in a specific support framework, known as “Staff Care”.

Chief Editor Boris Martin and his team decided to turn the spotlight on mental health to give it the place it deserves, taking care to show the plurality of this discipline and the different practices that can be observed in crisis areas.

This issue reflects the approach of AH’s Editorial Board, which is to say “one step aside, one step ahead”. Pierre Gallien and Stéphanie Stern, the report’s co-authors, and I started from the observation that although mental health is often mentioned, it is not really embodied in humanitarian structures. To borrow an old slogan: “mental health is everywhere, and at the same time nowhere”. Humanitarian aid has often focused on physical care, on caring for bruised and injured bodies, which is normal, but let’s just say that mental health came later and with greater difficulty.

This issue looks at how the discipline was introduced into the sector and what questions it raised within humanitarian organisations. I’m not going to quote all the articles, but the one devoted to the beginnings of mental health at Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Doctors Without Borders) is quite symbolic.

The first interventions of this type date back to the earthquake that devastated Armenia in 1988. It is important to emphasise that these activities were launched a year after the earthquake itself, in other words, once the bodies had been treated. We were not talking about “mental health” at that time, we were doing “psy“, or therapy. We deliberately used this vague term to avoid deciding on certain questions such as “psychiatry versus psychology”. Laure Wolmark’s article is very interesting in this respect, tracing this development within MSF and the debates it generated internally.

The World Health Organisation published its first report in 2001 to stress the importance of mental health, followed by a second report twenty years later, reminding us that NGOs have certainly made progress in this area, but that the question undoubtedly needs to be explored further.

Another important factor was the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact on mental health was felt globally and cut across all social categories and all cultures.

There is also the issue of climate change, which leads to eco-anxiety. It is a very Western concept, but it does bring us back to the idea that climate change affects countries in both the South and the North. Over the last few years, we have noticed that this issue has become an increasingly important part of the humanitarian agenda.

Breaking with certain archetypes

This issue provides a historical perspective on the development of this approach to mental health care, but also goes further by pointing out experiments that have not worked or that need to be revised.

The article by Camille Maubert and Bénédiction Kimathe illustrates another interesting aspect observed in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although there are institutions funding mental health programmes, the targeting of these funds at women and children reinforces the archetypal, albeit real, perception that women are often the victims and men the perpetrators. As a result, this focus does not allow us to consider one of the blind spots in these programmes, namely men’s mental health. If we add to this the “norms of masculinity” at community level and the material obstacles to men’s access to psychological care, we see that men are excluded de facto from the care pathways.

I will mention one final aspect, namely the need to break away from a single Western normative approach that presupposes the application of certain criteria. Mental health is also dealt with through local, more traditional approaches that are more accessible to local populations. These practices also deserve our attention. Mental health is not treated solely with drugs, particularly in countries in crisis where access to treatment is difficult in the long term.

This issue, like all issues in Alternatives Humanitaires, does not claim to be exhaustive, with six or seven articles. However, it does provide an introduction to the subject and invites readers to broaden their thinking on certain humanitarian challenges.

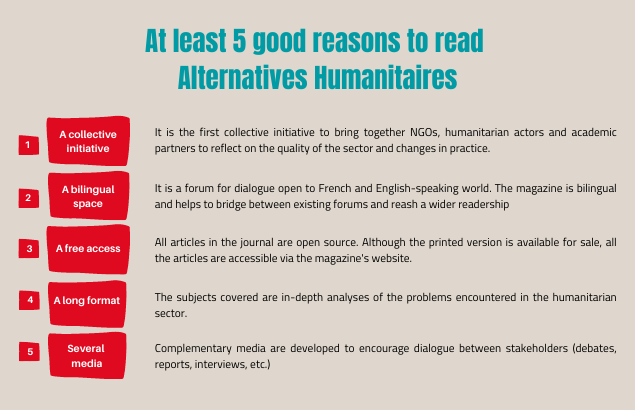

www.alternatives-humanitaires.org

Mental health at Première Urgence Internationale

In recent years, Première Urgence Internationale has also expanded its scope of action to include mental health and psychosocial support programs. Our services, enabled by the involvement of mental health experts and non-experts, adapt to the context of each mission, the needs of populations, their culture, and social norms. In the articles below, find out more about how we manage mental health in our humanitarian actions:

Break the stigma: let’s talk about mental health in Lebanon

Ukraine : the impact of conflict on mental health

France : mental health at the core of mission interventions

Field testimonies : the benefits of mental health support in an iraqi camp