Access Denied: A Palestinian farmer versus an Israeli settlement

In the West Bank, Israelis settlements keep growing despite the UN resolution adopted at the end of 2016. Première Urgence Internationale continues its activities for the victims of settlers attacks, through emergency response and advocacy actions. The teams accompany Palestinian farmers in the area of restricted access, such as Sami, who has seen his land being swallowed up by Israeli settlers.

Sami’s sister riding a donkey towards the edge of the family land, right next to the settlement. © Private collection / Sami Raddad.

Born in 1954 in Salfit, a district in the central part of Palestine, Sami Raddad, a farmer and a father of 9, spent his childhood growing up in the Jordanian-ruled hills of the West Bank. Along with his family, Sami farmed and took care of the family’s land where they grew various fruits and vegetables. “We would grow watermelons and cucumbers in this part, the rest was nothing but olive trees,” says Sami as he points at a map he is holding.

Sami’s land lays next to the town of Mas’ha, a nearby village less than a 5-minute drive from where we met him at his house in his hometown of Az-Zawiya. However, he still had to point at a map to show us his land instead of going there. It is not that Sami was tired of farming his land all day long that day, it is that he no longer has unimpeded access into his land anymore.

From privately owned land to illegal Israeli settlements

According to Applied Research Institute in Jerusalem (ARIJ), between the mid-1970s and the late 1980s, the Israeli authorities issued several orders to appropriate about a third of Mas’ha’s privately owned land, where they then established several illegal Israeli outposts. These outposts would later grow into settlements, built for the exclusive use of Israeli settlers. Under International Law, such settlements are illegal. According to the Fourth Geneva Convention—which Israel has signed—an occupying power “shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”

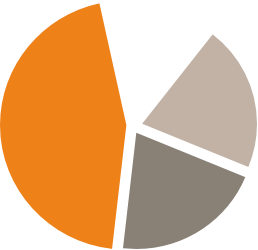

By 1977, the fences of the newly established settlement of “Elkana” swallowed up Sami’s farmland, almost entirely restricting the family’s access to their land. About 17 dunums (4.2 acres) of his land ended up on the other side of the illegal settlement’s fence, not only preventing him from carrying on his daily tasks of farming his land and cultivating his crops, but also draining his main source of income.

Four decades later, Sami’s land does not only remain within the fences of the Israeli settlement, it also now falls behind the Separation Wall, which the Government of Israel began constructing in the early 1990s, walling up the entire West Bank and swallowing up even more land. Sami can no longer enter his land whenever he wishes to, as access is restricted and is only possible through certain gates the Israeli authorities have installed in the Wall and only at certain times and hours during the year. Sami must apply for a permission with the Israeli authorities to be granted access to his land. Yet, most of his permit applications are refused.

Harassment and violence against civilian

Limiting Sami’s access to his land has not only prevented him from cultivating it, it has also increased the presence of Israeli settlers in its midst. Their presence is usually accompanied with attacks against his land and crops. Every year, when Sami manages to enter his land, he arrives to find his trees either sawn or burned. Sami already reported finding his land flooded with sewage water coming directly from the settlement of Elkana, seriously damaging the soil and drying up the trees, slowly killing them and poisoning their fruits.

In the olive harvest season (October to November), he always finds his trees with almost no olives on them, due to the fact that Israeli settlers enter his land a few days before his permit begins and steal his olives. Just last October, he barely found any olives left on the trees as they had been stolen by the settlers by the time he arrived. “I used to make about 40 gallons of olive oil every year from that piece of land. This year, I think I didn’t even make more than five.”

When the settlers set his land ablaze, Sami has to put it off himself, if he is lucky enough to have a permit on the day they decide to burn it. “As I was putting off the fire with a bucket of water I could see the Fire Department trucks of the settlement up the hill, they stood there without acting. They would have only interfered if the fire started reaching their houses.”

At certain times, while he is at his land fixing whatever he could, settlers would come and harass him, and often beat him up. Three years ago, settlers tried to kick him out of his land, shouting at him: “This is not your land, get out!” As he refused, two of them beat him on the head with a stick, causing a big incision right next to his eye.

“Taking any compensation would only legitimize their presence in my land”

Attacks on Sami’s land have been almost continuous and varied in nature, but they have one very specific goal: to discourage him from working in his land and severe his connection with it. Israeli violations have also taken the form of constructing roads that pass through his private property. Sami has lost a total of 5 dunums (1.2 acre) to the so-called ‘Cross-Samaria Highway’ or ‘Highway 5’, which goes through his land. Sami was offered compensations for these ‘public benefit projects’. However, he has always refused to receive any money in return for these violations, explaining that “taking any compensation would only legitimize their actions and their presence in my land.”

Following decades of settler attacks against him and his farmland—his only source of income—Sami approximates his financial losses at almost 2,000,000 Israeli shekels (about €520,000), an incredibly large sum for a farmer. As he looks through his window and sighs, Sami adds: “Even if I was allowed to enter my land as much as I can, I don’t think I can fix it much now, I’ve already spent all of my money on lawyers trying to take my land back.”

In the absence of serious efforts of the Israeli authorities to punish such attacks, settler violence will continue unabated. Sami does not know what will happen to his land in the future, he just knows it will be nothing good: “I’m very worried about what’s next. When we [the elderly] are gone, what will the youth do?”

Operational in the West Bank since 2002, and in the Gaza Strip since 2009, Première Urgence Internationale has developed integrated programmes to assist Palestinians affected by, or threatened with, protection risks. We help communities prepare for and respond to emergencies, we provide emergency response, including in-kind and cash-based interventions. We contribute to the humanitarian coordination mechanisms to promote human rights and advocate for the rights of Palestinians locally and internationally.

You can support our actions to protect Palestinian farmers victims of settler attacks. Make a donation and help us increase our responsiveness in the West Bank.