News

A mother’s burden: The complex interrelation between breastfeeding, infant health and maternal well-being

Publié le 01/08/2023

Decades of war and conflict have left deep marks on the rugged terrain of Afghanistan, on its people and on its infrastructure. The echoes of hardship can be heard in every corner of the landlocked country and witnessed in the cramped and run-down rooms of many Afghan hospitals.

The beds in the Therapeutic Feeding Unit (TFU) of one hospital in Nangarhar Province are filled two and three times over with malnourished children and their mothers. But only severe acute malnutrition (SAM) cases with complications are admitted to the hospital’s specialist unit.

Most of the women blame their dire economic situation for their children’s malnutrition, says Farah Première Urgence Internationale‘s Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) supervisor. “It is true that poverty is a big problem. Many pregnant women do not get the right amount of food or do not have a balanced diet during their pregnancy, but when I talk to these women, I learn that the reasons are multifaceted and often related to mental health issues, entrenched poverty, a lack of education as well as common misconceptions about breastfeeding practices.”

Tragically, many infants in Afghanistan are missing out on the life-saving benefits of breastfeeding. In Afghanistan, only 47.7% of infants are exclusively breastfed during the crucial first six months of life. The consequences of this shortfall are dire, as infants deprived of breastfeeding are at increased risk of malnutrition, weakened immune system and impaired cognitive development. In a society deeply affected by years of conflict, poverty, harmful traditional role models and a high prevalence of child marriage, maternal mental health problems remain widespread, often leaving mothers struggling with anxiety, loneliness, depression and a sense of helplessness – factors that can make it difficult to initiate and continue breastfeeding.

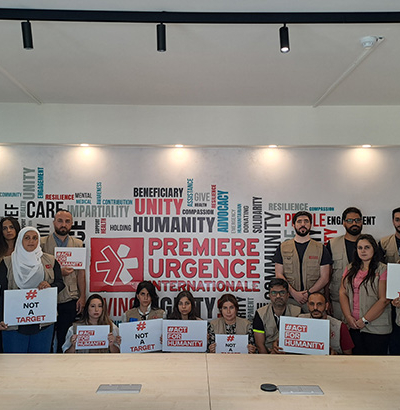

© Jessica Kühnle

16-year-old Nazia and her one-month-old girls have been at the UTH for 11 days. The girl, Husna, is severely malnourished because Nazia is unable to properly breastfeed her.

“After giving birth, I tried to breastfeed my baby, but she didn’t want to drink. So, I gave her to a relative and she started drinking her breast milk. I tried to breastfeed her again, but she still did not want to drink. After six days, I started giving her powdered milk. Her health deteriorated. She cried a lot and did not gain weight. A doctor from my village advised me to take her to the hospital where she could receive specialized care. When I arrived at the hospital, Husna was very weak and could hardly breathe,” says Nazia.

Talking to Nazia, however, reveals that the young mother struggles with loneliness and lack of support from her family, especially her mother. After getting married, Nazia moved in with her husband and away from her parents. Now she is without the support of her mother and sisters, she has no one to give her advice on breastfeeding and how to be with her child.

“I don’t have anyone, I’m alone. There is no one to support me with my child and tell me how to breastfeed. We are also very poor people; I can’t even afford clothes for myself and my baby. The neighbors would bring me clothes,” says Nazia when Farah asks her how she feels.

Farah can link many of the causes of severe malnutrition in children under five to stress and lack of knowledge. Twenty-five-year-old Darya, who came to the TFU with her two children, also sees poverty as the only reason for the critical health condition of seven-month-old Noman. He suffers from severe acute malnutrition with complications. His little body is also battling meningitis and pneumonia, too. Farah, however, also learns from talking to Darya that although the young mother is aware of the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, she has not been able to feed her son regularly and exclusively.

© Jessica Kühnle

Exclusive and continued breastfeeding for the first six months of life provides infants with vital nutrients, antibodies and enzymes that protect them from infection, strengthen their immune system and could help prevent 13% of deaths among children under five years. It acts as a shield against diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, which are often responsible for infant mortality in regions struggling with poverty and limited access to health facilities.

“I was aware that the boy was not getting enough breast milk and I tried to find out why, as Darya had already received advice from the mobile health team that visits her village once a week. I soon realized that Darya was also suffering from a lot of stress, anxiety and feeling overwhelmed,” says Farah.

During their conversation, Darya explains that her situation is very challenging: “I have to take care of my seven children, two of whom, my two youngest, are sick. I don’t have time for myself or my husband. By the time I manage to get one child to sleep, the next one is crying. I can’t sleep, I don’t know where to go, I don’t know what to do. I don’t even have time to see my mother!”

Stress and feeling overwhelmed can have a detrimental effect on a mother’s ability to breastfeed her baby. Stress can reduce the production of oxytocin and prolactin, the hormones responsible for milk production and the let-down reflex. As a result, mothers may experience reduced milk supply, making it difficult to provide enough nourishment for the baby, which can lead to self-doubt and anxiety about the mother’s ability to breastfeed successfully. Too much stress can also cause tension in the mother’s body, making it difficult for the baby to latch on properly.

“When a mother is stressed or overwhelmed, it can be difficult to focus on the breastfeeding process, which requires patience and concentration. In addition, breastfeeding is not just about feeding your baby, it also fosters a strong emotional bond between mother and baby. However, stress can interfere with this emotional connection, and make it difficult for the mother to feel relaxed and connected during breastfeeding sessions,” explains Farah.

© Jessica Kühnle

Farah knows these connections only too well. That is why she and two other psychosocial support (PSS) providers at the TFU help mothers through these difficult times. PSS practitioners like them play a crucial role in helping mothers through times of stress and overwhelm, especially when it comes to breastfeeding. Through counselling, they can provide a safe and sensitive space for mothers to express their feelings, concerns and challenges around breastfeeding. They can help mothers overcome self-doubt and anxiety, and foster a positive attitude that promotes successful breastfeeding.

Farah and her colleagues also teach good breastfeeding practices, such as proper latching and positioning, to ensure optimal nutrition for the baby. They teach mothers the importance of recognizing hunger cues and how to establish a breastfeeding routine that meets the needs of both mother and baby. They also teach relaxation techniques to reduce stress during breastfeeding sessions and provide guidance on maintaining good physical health to support milk production.

Première Urgence Internationale, known in Afghanistan as Première Urgence – Aide Médicale Internationale (PU-AMI), provides psychosocial support to pregnant and lactating women in six provinces through static and mobile health facilities. In 2022, more than 23,800 women received individual and group counseling.

All names have been changed.